Understanding BIOS Types - Legacy BIOS, EFI, and UEFI

Introduction

This blog post aims to help illuminate the differences between Legacy BIOS, EFI, and UEFI. Personally, it’s a topic and technical evolution I’ve taken for granted and one which I wanted to better understand.

A computer’s embeeded firmware is the first code that runs when you power on your computer. Many of us take this for granted. However, it performs a critical role in the computer’s lifecycle. It is code that initializes hardware and hands off control to the operating system.

Firmware, sometimes termed “BIOS”, can be classified into three main types: Legacy BIOS, EFI, and UEFI. These have evolved significantly in the last 15 years, and most computers still support all 3. So it can be a source of confusion for developers, secutiy pros, and admins. Understanding differences matters for:

- Security (Secure Boot, rootkit protection)

- Compatibility (older vs newer hardware/OS)

- Performance (boot times, disk support)

- Troubleshooting boot issues

Legacy BIOS - The Original

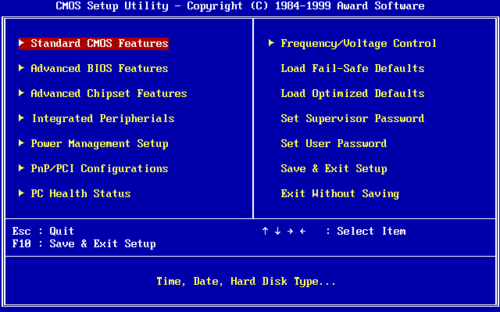

A typical Legacy BIOS setup screen - text-only interface navigated with keyboard. Source: Wikimedia Commons

A typical Legacy BIOS setup screen - text-only interface navigated with keyboard. Source: Wikimedia Commons

What It Is

BIOS stands for Basic Input/Output System. It dates all the way back to 1981 (IBM PC). Legacy BIOS ran as 16-bit real mode processor operation and was written in assembly language. It is stored on ROM/EEPROM chip on motherboard

How It Works

When a computer is booted, it loads a POST (Power-On Self-Test) program in the EEPROM. This program searches for bootable device in configured order. It then loads the first 512 bytes of disk (Master Boot Record / MBR). This MBR contains bootloader code plus the all important partition table, which lays out the operating system volumes and other storage primitives. After analyzing these partitions, the Bootloader loads the operating system.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations with the Legacy BIOS approach. First, the MBR partition scheme is limited to a maximum of 4 primary partitions and a maximum disk size of 2.2 TB (2^32 sectors x 512 bytes). As computer storage technology has significantly advanced in the last 20 years, we’ve hit this limit.

Next, Legacy BIOS only supports a 1 MB address space constraint. This limits the complexity and feature set of the BIOS programming. This can be.

Third, there is no native security features (no Secure Boot). SecureBoot is a feature that prevents the computer from running untrusted code in the kernel, a critial safeguard against kernel ring level 0 attacks (rootkits, others). Check out my blog post on Detecting Secure Boot with Go for technical details.

Fourth, Legacy BIOS has zero network capability built-in. This means not network booting, a critical tool in enterprise systems. Many companies and admins rely on centralized boot servers for provisioning or managing zero trust environments.

Fifth, Legacy BIOS - Text-based interface only. This limits the user experience and UI abilities like search.

Sixth, Legacy BIOS is slow! It uses sequential initialization and is limited to 16bits in bandwith. That slows things down.

Seventh, and finally Legacy BIOS offers no standardized way to extend functionality. Vendors who resell motherboards aren’t able to extend the BIOS functionality of the base chipset. This limits a lot of features and updates to other hardware in the stack.

EFI - The Transition

To address these limitations, the community proposed EFI, the Extensible Firmware Interface. This was developed by Intel starting in mid-1990s, originally for Itanium (IA-64) servers. The first specification for EFI was released 2000 and is an Intel’s proprietary standard. Key improvements over Legacy BIOS include 32-bit and 64-bit operation. Additionally, EFI uses GPT – GUID Partition Table – which supports up to 128 partitions amd disks up to 9.4 ZB (zettabytes)! EFI is also a modular, driver-based architecture which allows customization and hardware specific configs. It also provides a pre-boot environment with networking capability and graphical interface support

However, despite its important advances, EFI was quickly superseded. Why? It remained Intel-controlled which limited industry adoption. This also cripled broader vendor support which led to formation of UEFI Forum in 2005

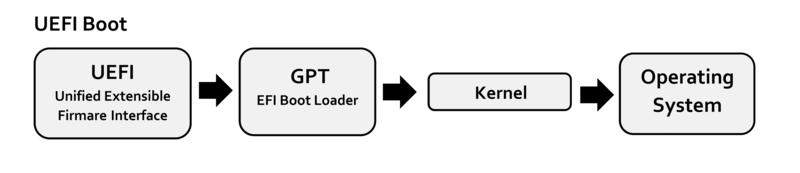

EFI boot flowchart showing the initialization phases from power-on to OS handoff. Source: Wikimedia Commons

EFI boot flowchart showing the initialization phases from power-on to OS handoff. Source: Wikimedia Commons

UEFI - The Modern Standard

Today, modern BIOS uses UEFI, the Unified Extensible Firmware Interface. It is a true industry consortium standard (not single vendor). UEFI Forum members include AMD, Apple, Dell, HP, Intel, Lenovo, and Microsoft. The current spec, UEFI 2.10 was released 2022 and is backwards compatible with EFI.

Here is a summary of the UEFI architecture and features:

Architecture

UEFI represents a fundamental rethinking of how firmware should work. Unlike Legacy BIOS, which was essentially a monolithic blob of assembly code, UEFI provides a proper pre-boot execution environment. Think of it as a mini operating system that runs before your actual operating system.

One of the smartest decisions the UEFI designers made was writing the specification to support C code rather than assembly. This might seem like a minor detail, but it’s huge. C is portable and maintainable. It means firmware developers aren’t locked into arcane assembly tricks, and code can be reasoned about, tested, and audited much more easily. From a security perspective, this is a win.

UEFI operates in either 32-bit or 64-bit mode depending on the system architecture. This eliminates the bizarre real-mode limitations that plagued Legacy BIOS. No more 1 MB address space constraints - UEFI can address the full memory space of modern systems.

The EFI System Partition (ESP) is another architectural cornerstone worth understanding. This is a dedicated FAT32-formatted partition on your boot disk that stores bootloaders, drivers, and utilities. If you’ve ever poked around your disk partitions and wondered what that ~100-500 MB FAT32 partition was doing there, now you know. The ESP provides a standardized location for boot assets that any UEFI-compliant system can find and use. This standardization is what allows you to boot multiple operating systems cleanly, or recover a bricked system with a USB drive.

Key Features

Secure Boot is probably the core feature that most people associate with UEFI. It provides cryptographic verification of boot software before execution. Every bootloader, driver, and kernel must be signed with a trusted key, and the firmware verifies these signatures before allowing code to run. This is your first line of defense against bootkits and rootkits - malware that tries to load before the operating system and hide from security software. Without Secure Boot, an attacker who compromises your boot process owns your machine at the deepest level. Check out my blog post on Detecting Secure Boot with Go if you want to dig into the implementation details.

Fast boot times come from parallel initialization. Legacy BIOS initialized hardware sequentially - one device after another. UEFI can initialize multiple devices simultaneously. On modern systems with NVMe drives, you can go from power button to login screen in seconds. This isn’t just a nice-to-have; in enterprise environments, faster boot times mean faster recovery from reboots and less downtime during patching cycles.

Network boot (PXE) is built directly into the UEFI specification. For enterprise admins, this is essential. You can provision hundreds of machines from a central boot server, deploy images, run diagnostics, or implement zero-trust boot verification - all without touching physical media. Legacy BIOS required vendor-specific extensions for network boot, and they were often unreliable.

The graphical setup utility with mouse support might seem like a cosmetic improvement, but it dramatically lowers the barrier to firmware configuration. No more memorizing which F-key does what or navigating cryptic text menus with arrow keys. Modern UEFI setups look and feel like actual applications.

UEFI Shell is an underappreciated feature. It’s a command-line environment that runs before the OS, giving you scripting capabilities for diagnostics, disk management, and system configuration. If you’ve ever had to recover a corrupted bootloader or debug hardware issues, having a proper shell environment at the firmware level is invaluable.

The modular driver model means hardware vendors can ship UEFI drivers for their devices that load during the pre-boot phase. This allows new hardware to work out of the box without OS updates. It also means your UEFI setup can display on your fancy new GPU or read from your exotic storage controller before the OS even loads.

ACPI and SMBIOS table support provides standardized ways for firmware to communicate hardware configuration to the operating system. This is the plumbing that makes features like power management, thermal control, and hardware discovery work reliably across different vendors.

Finally, Capsule updates allow firmware updates to be delivered through the operating system rather than requiring manual BIOS flashing. Windows Update can push firmware patches just like any other update. This is critical for security - the easier it is to patch firmware, the more likely people are to actually do it. Unpatched firmware vulnerabilities are a real and growing attack vector.

The UEFI boot process showing the stages from power-on through OS handoff. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The UEFI boot process showing the stages from power-on through OS handoff. Source: Wikimedia Commons

References

- UEFI Forum Specifications: https://uefi.org/specifications